A three-judge panel on the 9th Circuit unanimously overturned the district court’s 2016 decision in the “Stairway to Heaven” copyright infringement case.[1] The case involved two songs: Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven” and Spirit’s “Taurus.” The jury found that the opening guitar melody of “Stairway” was not “extrinsically similar” to a portion of the instrumental-song “Spirit.”[2] However, for reasons discussed below, the case was remanded for a new trial.[3]

The late Randy Wolfe, guitarist of the band Spirit, composed the song “Taurus” in late 1966.[4] In December 1967, the copyright was filed for “Taurus,” listing Wolfe as the author.[5] At that point, “Taurus” was transcribed into sheet music and deposited with the Copyright Office.[6] Because the song was filed prior to 1972,[7] the district court ruled that the jurors could not listen to Spirit’s recordings of “Taurus,” but would rather use the deposited sheet music and live renditions (performed by music experts—some live in the courtroom)[8] as baselines in determining whether “Stairway” was substantially similar to “Taurus.”[9]

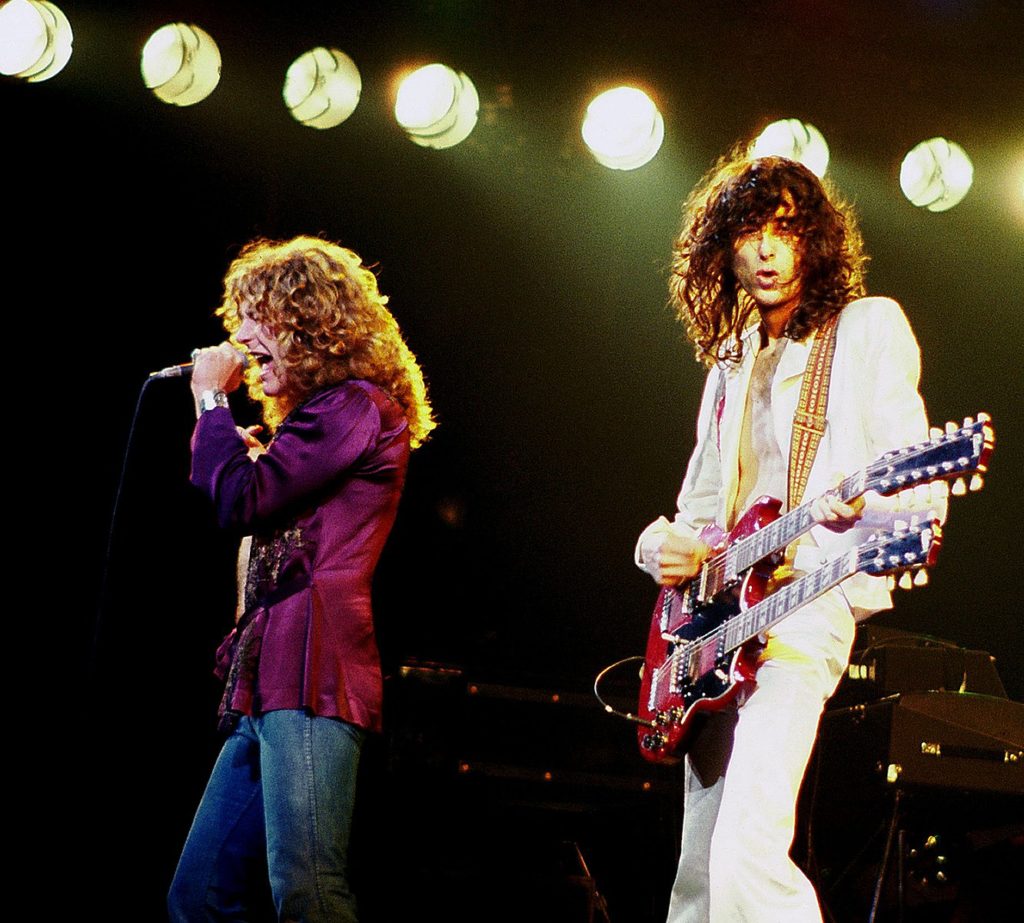

At trial, Michael Skidmore (“Skidmore”), the plaintiff, objected to this decision. Skidmore stated that Jimmy Page, the Led Zeppelin guitarist and named plaintiff, should have been able to listen to Spirit’s recordings of “Taurus” in order to “prove access”—that is, to determine whether Page had heard the song before.[10] The district court determined that it would be prejudicial for the jury to hear the recordings, but held Page could listen outside the jury’s presence, to then be questioned by Skidmore about the recordings in front of the jury.[11] Though the jury ultimately found that Page did have access to “Taurus” (Page even conceded that he owned the album containing “Taurus” in his music collection, but had never listened to it), the jury also found that the two songs were not “substantially similar.”[12]

On appeal, Skidmore argued (in part) that the sound recording should have been allowed to be played (in front of the jury) in order to prove access.[13] He also argued that some of the jury instructions were erroneous.[14] The 9th Circuit agreed with these challenges.[15]

To succeed on a copyright infringement claim, a plaintiff must establish the following elements: “(1) that he owns a valid copyright in his [work], and (2) that [defendant] copied protected aspects of the [plaintiff’s work].”[16] Since the first element had already been established, the 9th Circuit did not address it as an issue.

The second element, concerning actual infringement, involves two components: “copying” and “unlawful appropriation.”[17] First, a plaintiff must prove that the defendant “copied” his or her work. If the defendant composed a song independently (i.e. without having heard the original), any similarities would only be coincidental.[18] When there is no direct evidence of copying (as was the case in Skidmore), the plaintiff “can attempt to prove it circumstantially by showing that the defendant had access to the plaintiff’s work and that the two works share similarities probative of copying.”[19] “’When a high degree of access is shown,’ a lower amount of similarity is needed to prove copying.”[20] In short, “[t]o prove copying, the similarities between the two works need not be extensive, and they need not involve protected elements of the plaintiff’s work. They just need to be similarities one would not expect to arise if the two works had been created independently.”[21]

Unlawful appropriation requires a stronger demonstration of similarity than “copying” does.[22] In examining unlawful appropriation, the 9th circuit employs “extrinsic” and “intrinsic” tests to determine whether “an allegedly infringing work is substantially similar to the original work.”[23] The extrinsic test:

is an objective comparison of protected areas of a work. This is accomplished by “breaking the works down into their constituent elements, and comparing those elements” to determine whether they are substantially similar. Only elements that are protected by copyright are compared under the extrinsic test.[24]

In other words, the extrinsic test “assesses the objective similarities of the two works, focusing only on the protect-able elements of the plaintiff’s expression.”[25]

The jury found that “Stairway” had not passed the extrinsic test, and therefore did not constitute unlawful appropriation.[26] The circuit court decided that certain jury instructions could have mislead the jury, and thus warranted a new trial.[27] In essence, the district court led the jury to believe that elements of music in the public domain and certain types of musical sequences were not protected by copyright.[28] However, elements of music in the public domain are actually copyright protected if their selection and arrangement could be considered original.[29] These jury instructions undercut Skidmore’s arguments regarding extrinsic similarity, and were therefore prejudicial.[30] Since Skidmore’s extrinsic similarity arguments were undermined, the works were never examined under the intrinsic test (the intrinsic test is concerned with whether the “feel” of the works are substantially similar—a more subjective analysis).[31]

Another challenge Skidmore raised was that the district court abused its discretion in not allowing Jimmy Page to listen to “Taurus” in front of the jury to prove access (as opposed to an unlawful appropriation/similarity determination).[32] “The district court excluded the sound recordings under Federal Rule of Evidence 403, finding that ‘its probative value is substantially outweighed by danger of . . . unfair prejudice, confusing the issues, [or] misleading the jury . . . .’”[33] The circuit court held that the risk of jury confusion was relatively small, and certainly could have been further mitigated by the judge telling the jury that the recording playback was for purposes of proving access and not substantial similarity.[34] The probative value of the jury seeing Page listening to the recording and then observing Skidmore’s questioning of him outweighed the relatively minuscule risk of jury confusion.[35] Though the circuit court acknowledged that the original jury had already determined that Page had access to “Taurus” and therefore did not affect the verdict anyway, the court addressed the issue because it felt the district court had abused its discretion in excluding the evidence (of observing Page listen to the recording and the subsequent questioning), and the issue will likely arise again at retrial.[36]

How will this appellate decision affect the retrial?

When the case returns to trial, the jury will continue to not be able to hear Spirit’s original album recording of “Taurus” (in order to judge its substantial similarity to “Stairway”). The jury will be able to hear the recording in order to weigh access, but there might be measures in place to make sure the jury doesn’t listen too closely.[37][38] The jury will also be instructed more clearly on what is and what isn’t copyright protected and how the extrinsic test should be administered.

If the new jury finds that the two songs are extrinsically similar, it would open the doors to the intrinsic test. The intrinsic test examines whether the “total concept and feel of the works [are] substantially similar.”[39] After the 9th Circuit upheld the “Blurred Lines”[40] verdict in March, critics of the decision argued that it too greatly expanded the jurisdiction’s definition of infringement, leaving artists vulnerable.[41] As this intrinsic test is more intuitional than scientific, it could weigh the odds in Skidmore’s favor.

If Skidmore wins, it would potentially mean that Randy Wolfe would get songwriting credit for, arguably, one of the most well-known songs of all time. Wolfe’s estate would also earn a portion of any revenue “Stairway” produces in the future.[42]

Below is a comparison of the two songs. Do you think the “feel of the works are substantially similar?”

Jordan Davis is a second-year law student at Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law and a Staff Editor of the Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal. He enjoys listening to the recordings of Led Zeppelin (and Spirit) and looks forward to pursuing a career in real estate litigation.

[1] Jonathan Stempel, Led Zeppelin must face new trial claiming it stole ‘Stairway’ riff, Reuters (Sep. 28, 2018 1:39 PM) https://www.reuters.com/article/us-music-ledzeppelin/led-zeppelin-must-face-new-trial-claiming-it-stole-stairway-riff-idUSKCN1M82ET; Skidmore v. Led Zeppelin, No. CV 15-3462 RGK (AGRx), 2016 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 51006 (C.D. Cal. Apr. 8, 2016).

[2] Daniel Siegal, Led Zeppelin Triumphs In ‘Stairway’ Rip-Off Trial, Law360 (June 23, 2016, 1:17 PM), https://0-www-law360-com.ben.bc.yu.edu/articles/809896/led-zeppelin-triumphs-in-stairway-rip-off-trial.

[3] Sudhin Thanawala, Associated Press, New trial ordered in ‘Stairway to Heaven’ copyright lawsuit, L.A. Times (Oct. 2, 2018), http://www.latimes.com/sns-bc-us–stairway-to-heaven-20180928-story.html.

[4] Skidmore v. Led Zeppelin, Nos. 16-56057, 16-56287, 2018 U.S. App. LEXIS 27680, at *4 (9th Cir. Sep. 28, 2018) [hereinafter “Skidmore”]. The plaintiff, Michael Skidmore, is a working trustee for Randy Wolfe’s trust.

[5] Id.

[6] Id.

[7] Sound recordings only became subject to federal copyright protection after the enactment of The Sound Recording Act of 1971 (which was enacted several years after the song’s original recording).

[8] Edvard Pettersson, The Washington Post, Led Zeppelin to face retrial over ‘Stairway’ theft claims, L.A. Times (Sep. 28, 2018 12:15 PM), http://www.latimes.com/ct-ent-lep-zeppelin-stairway-retrial-20180928-story.html.

[9] Skidmore v. Led Zeppelin, Nos. 16-56057, 16-56287, 2018 U.S. App. LEXIS 27680, at *7-*8 (9th Cir. Sep. 28, 2018).

[10] Skidmore at *10-11. See also Rentmeester v. Nike, Inc., 883 F.3d 1111, 1117 (9th Cir. 2018) (“When the plaintiff lacks direct evidence of copying, he can attempt to prove it circumstantially by showing that the defendant had access to the plaintiff’s work and that the two works share similarities probative of copying.”).

[11] Skidmore at *10.

[12] Id. at *11.

[13] Id. at *39.

[14] Id. at *14 (stating “that the district court erred by failing to give an instruction that selection and arrangement of otherwise unprotectable musical elements are protectable.”).

[15] It should be noted that the 9th Circuit affirmed these specific contestations, but disagreed with several others. See Skidmore.

[16] Rentmeester v. Nike, Inc., 883 F.3d 1111, 1116 (9th Cir. 2018) (citing Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service Co., 499 U.S. 340, 361, 111 S. Ct. 1282, 113 L. Ed. 2d 358 (1991)). See also Shaw v. Lindheim, 919 F.2d 1353, 1356 (9th Cir. 1990).Bottom of Form

[17] Rentmeester v. Nike, Inc., 883 F.3d at 1117.

[18] Skidmore at *13 (“[I]ndependent creation is a complete defense to copyright infringement.”).

[19] Id. (quoting Rentmeester, 883 F.3d at 1117) (emphasis added). See also Bernal v. Paradigm Talent & Literary Agency, 788 F. Supp. 2d 1043, 1053 (C.D. Cal. 2010) (“To prove access, Plaintiff must show that the Defendants had a ‘reasonable opportunity’ or ‘reasonable possibility’ of viewing Plaintiff’s work prior to the creation of the infringing work.”); see also Stabile v. Paul Smith Ltd., No. CV 14-3749, 2015 WL 5897507, at *9 (C.D. Cal. July 31, 2015) (“[A] plaintiff can prove copying even without proof of access if he can show that the two works are not only similar, but are so strikingly similar as to preclude the possibility of independent creation.”). Bottom of Form

[20] Skidmore at *13 (quoting Rice v. Fox Broadcasting Co., 330 F.3d 1170, 1178) (citation omitted). This is known as the “inverse ratio rule.” On appeal, Skidmore argued that the district court erred by not including the “inverse ratio rule” in the jury instruction. However, the inverse ratio rule only applies to the “copying” component, not “unlawful appropriation.” The jury in Skidmore never had to deliberate on the “copying” component. See Skidmore, at *26, *28 (“Because we are remanding for a new trial, however, we note that in a case like this one where copying is in question and there is substantial evidence of access, an inverse ratio rule jury instruction may be appropriate.”).

[21] Rentmeester, 883 F.3d at 1117.

[22] Skidmore at *13 (citing Rentmeester, 883 F.3d at 1117).

[23] Skidmore at *14.

[24] Skidmore at *14 (quoting Swirsky v. Carey, 376 F.3d 841, 845 (9th Cir. 2004)).

[25] Rentmeester v. Nike, Inc., 883 F.3d 1111, 1118 (9th Cir. 2018)Bottom of Form (citing Cavalier v. Random House, Inc., 297 F.3d 815, 822 (9th Cir. 2002)). Since the jury found that there was no extrinsic similarity, it did not have to determine whether there was intrinsic similarity.

[26] Skidmore at *27 (“[T]he jury ended its deliberations after deciding that ‘Taurus’ and ‘Stairway to Heaven’ were not substantially similar under the extrinsic test.”).

[27] See Skidmore at *23 (“Jury Instruction No. 16 included an instruction that “common musical elements, such as descending chromatic scales, arpeggios or short sequences of three notes” are not protected by copyright. This instruction runs contrary to our conclusion in Swirsky that a limited number of notes can be protected by copyright.”).

[28] Id. at *25 (“Jury Instruction No. 20 compounded the errors of that omission by furthering an impression that public domain elements are not protected by copyright in any circumstances.”).

[29] Id. at *25.

[30] Jury Instruction No. 16 and Jury Instruction No. 20.

[31] See Skidmore at *14-15, 20. See also Three Boys Music Corp. v. Bolton, 212 F.3d 477, 485 (9th Cir. 2000). See also infra pp. 8-9.

[32] Skidmore at *39 (“Although Skidmore’s counsel was permitted to play recordings for Page outside the presence of the jury, who was then questioned about them in front of the jury, Skidmore argues that the jury could not assess Page’s credibility without observing him listening to the recordings and then answering questions about the recordings.”).

[33] Skidmore at *40 (quoting Fed. R. Evid. 403).

[34] Id.

[35] Id.

[36] Skidmore at *39 (“As the jury ultimately found that both Plant and Page had access to “Taurus,” any error in precluding the recordings was harmless. As this issue will likely arise again at retrial, we address whether the district court abused its discretion.”).

[37] Perhaps the recording will be played at a low volume or through headphones for Page to hear; this is mere speculation.

[38] Again, the copyright only protects the deposited sheet music.

[39] Three Boys Music Corp. v. Bolton, 212 F.3d 477, 485 (9th Cir. 2000).

[40] Williams v. Gaye, 885 F.3d 1150 (9th Cir. 2018).

[41] See Taylor Turville, Emulating vs. Infringement: the Blurred Lines of Copyright Law, 38 Whittier L. Rev. 199, 222 (2018); Joseph M. Santiago, The Blurred Lines of Copyright Law: Setting a New Standard for Copyright Infringement in Music, 83 Brook. L. Rev. 289, 322 (2017). C.f. Mike Masnick, 9th Circuit Never Misses A Chance To Mess Up Copyright Law: Reopens Led Zeppelin ‘Stairway To Heaven’ Case, Techdirt (Oct. 1, 2018 9:33 AM), https://www.techdirt.com/articles/20180928/18021040739/9th-circuit-never-misses-chance-to-mess-up-copyright-law-reopens-led-zeppelin-stairway-to-heaven-case.shtml.

[42] Randy Lewis & Joel Rubin, Everything you need to know about Led Zeppelin’s ‘Stairway to Heaven’ copyright trial, L.A. Times (Jun. 14, 2016 9:33 AM), http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/music/la-et-ms-led-zeppelin-copyright-trial-info-20160614-snap-story.html (“[G]oing forward, any percentage of revenue coming out of sales or airplay of the song could add up to a significant windfall for the estate of Wolfe . . . .”). Wolfe would only receive “Stairway” revenue from a few years prior to the case because of the statute of limitations.