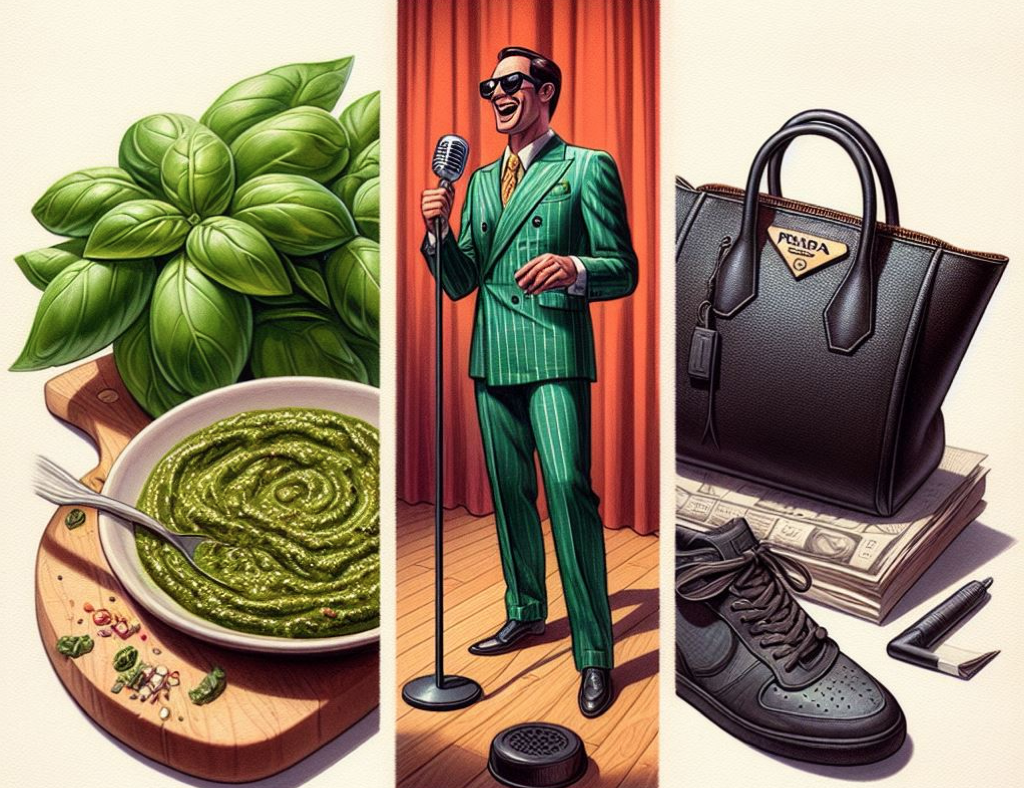

From Punchlines to Pesto to Prada: Exploring Intellectual Property’s Negative Space

- What is Intellectual Property?, World Intell. Prop. Org., https://www.wipo.int/about-ip/en/ (last visited Mar. 21, 2024) [https://perma.cc/2MLN-SLUV].

- Kal Raustiala & Christopher Sprigman, The Piracy Paradox: Innovation and Intellectual Property in Fashion Design, 92 Va. L. Rev. 1687, 1764 (2006) (coining and defining the term “negative space” in the intellectual property context).

- Id. at 1777.

- Id.

- See generally Omri Rachum-Twaig, The Case Against Copyright Protection of Food, 63 IDEA: The IP L. Rev. 138 (2023).

- Id.

- See Copyright Protection in Recipes, Copyrightlaws.com (Oct. 12, 2022), https://www.copyrightlaws.com/copyright-protection-recipes/ [https://perma.cc/FG9Z-M7W3]; see also Tomaydo-Tomahhdo L.L.C. v. Vozary, 82 N.E.3d 1180 (Ohio Ct. App. 2017) (holding “the list of ingredients is merely a factual statement, and as previously discussed, facts are not copyrightable. Furthermore, a recipe’s instructions, as functional directions, are statutorily excluded from copyright protection.”).

- See for example Stacey Leasca, Celebrity Chefs Are Bringing Their Recipes to Pinterest so You Can Be a Better Home Cook, Travel+Leisure (Jul. 16, 2020), https://www.travelandleisure.com/food-drink/cooking-entertaining/pinterest-chefs-at-home-recipe-series [https://perma.cc/PJN7-6BLG] (“The coronavirus pandemic has truly changed our daily lives. Since mid-March, people around the world switched up their work routines, canceled travel plans, and, according to Pinterest, starting cooking at home a lot more often. As the social media site explains, searches for ‘easy at-home recipes’ have increased 12-fold over the last few months. And because you’re searching for it, Pinterest wants to help you become even more skilled in the kitchen with its new Chefs at Home series.”).

- Supra note 1 at 1762 (“The fashion industry flourishes despite a near-total lack of protection for its core product, fashion designs. That this low-IP regime has remained stable over more than half a century, and that significant innovation and investment is undertaken within it, is a profound, if overlooked, challenge to the standard account of IP rights. We believe that the models we have advanced to explain the fashion industry’s peculiar innovation ecology are valuable in themselves, in that they help explain an important anomaly in American law.”)

- Rachel Kim, How is Fashion Protected by Copyright Law?, copyrightalliance (Feb. 10, 2022), https://copyrightalliance.org/is-fashion-protected-by-copyright-law/ [https://perma.cc/HD32-KX5P].

- Barbara Kolsun & Douglas Hand, The Bus. & L. of Fashion & Retail (2020) at 15–16.

- Id. at 94.

- See generally Rose Lagacé, The Devil Wears Prada Cerulean Sweater Monologue, Art Departmental (Jul. 17, 2017), https://artdepartmental.com/blog/devil-wears-prada-cerulean-monologue/ [https://perma.cc/J5K2-BJG7] (“You’re also blithely unaware of the fact that, in 2002, Oscar de la Renta did a collection of cerulean gowns, and then I think it was Yves Saint Laurent, wasn’t it? who showed cerulean military jackets. . . . And then cerulean quickly showed up in the collections of eight different designers. Then it filtered down through the department stores and then trickled on down into some tragic casual corner where you, no doubt, fished it out of some clearance bin. However, that blue represents millions of dollars of countless jobs”).

- Hannah Pham, Intellectual Property In Stand-Up Comedy: When #FuckFuckJerry Is Not Enough, Harv. J.L & Tech. Dig. (2020).

- Brian M. Hughes, The Psychology of Stand-Up Comedy, PsychologyToday (Jun. 5, 2016), https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/homeostasis-disruptor/201606/the-psychology-stand-comedy-0 [ (“The success of live comedy depends on a performer's ability to “work” an audience.”).

- Id.

- See generally Scott Woodard, Who Owns a Joke? Copyright Law and Stand-Up Comedy, 21 Vand. J. of Ent. & Tech. L. 1041 (2020) (“This article undertakes a comparative analysis of two copyright regimes—from the United States and the United Kingdom—and measures their relative similarities and differences. From this comparison, this article explains how stand-up comedians, a group of artists who have traditionally believed their work was incapable of receiving copyright protection, could receive copyright protection for their jokes in both jurisdictions.”).

- Elizabeth L. Rosenblatt, A Theory of IP’s Negative Space, 34 Colum. J. of L. & the Arts 317, Vol. 34 (2011)

(“Many areas of creation function in the absence of intellectual property protection. A smaller group—those residing in IP’s negative space—are enhanced by that absence.”).

- See generally Christopher Jon Sprigman, Conclusion: Some Positive Thoughts about IP’s Negative Space, in Creativity without L. (Kate Darling & Aaron Perzanowski eds., 2017)

- What If We Didn’t Have Intellectual Property Laws?, The Michelson Inst. for Intell. Prop. (Jul. 27, 2023), https://michelsonip.com/what-if-we-didnt-have-intellectual-property-laws/ [https://perma.cc/VW3H-F75R] (“Without the promise of exclusive rights and the potential to profit from their creations, many innovators might be discouraged from investing in new ideas and technologies.”).